Click to set custom HTML

ARRANMORE ~ Population approximately 600 +

Árainn Mhór meaning "Large Ridge"

Arranmore Island

Arranmore Island lies 5 km/3 miles off the coast of the port of Burtonport, County Donegal and can be reached by the ferry which operates from Burtonport daily. At seven square miles in size, the island is the second biggest inhabited island of Ireland and the biggest of the Donegal islands.

Before the Flight of the Earls at the start of the 17th century, the island was controlled by the O'Donnell Clan (of Donegal Castle) and was known as Ára Uí Dhomhnaill which means in English "O'Donnell's Aran". During the Plantation of Ulster in the 17th century the island was granted to Lord Conyngham as was much of west Donegal at that time. It was during his ownership of the island, a place he never once visited it must be noted, many of the people of the island were forced to leave their homes starving as they were because of the Irish Famine. Many died on the island, many in the poorhouse in Glenites and many aboard ships to America and Canada. Many of the islanders who managed the journey of emigration ended up on Beaver Island with whom Arranmore is now twinned.

There are seven lakes on the island and Arranmore's lakes are some of the only in Europe where rainbow trout breed naturally (the lakes also yield brown trout). The island is a haven for walkers, hikers, bird-watchers and many other pursuits including deep-sea angling, scuba diving, rock climbing and even taking Irish language and cultural courses.

Scroll down to end to see lots of photographs of Arranmore Island and a google map showing location.

Before the Flight of the Earls at the start of the 17th century, the island was controlled by the O'Donnell Clan (of Donegal Castle) and was known as Ára Uí Dhomhnaill which means in English "O'Donnell's Aran". During the Plantation of Ulster in the 17th century the island was granted to Lord Conyngham as was much of west Donegal at that time. It was during his ownership of the island, a place he never once visited it must be noted, many of the people of the island were forced to leave their homes starving as they were because of the Irish Famine. Many died on the island, many in the poorhouse in Glenites and many aboard ships to America and Canada. Many of the islanders who managed the journey of emigration ended up on Beaver Island with whom Arranmore is now twinned.

There are seven lakes on the island and Arranmore's lakes are some of the only in Europe where rainbow trout breed naturally (the lakes also yield brown trout). The island is a haven for walkers, hikers, bird-watchers and many other pursuits including deep-sea angling, scuba diving, rock climbing and even taking Irish language and cultural courses.

Scroll down to end to see lots of photographs of Arranmore Island and a google map showing location.

BEAVER ISLAND & ARRANMORE ISLAND

Beaver Island Memorial, Arranmore

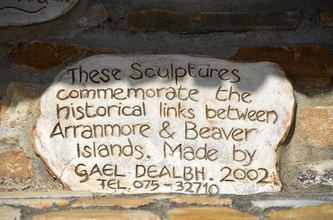

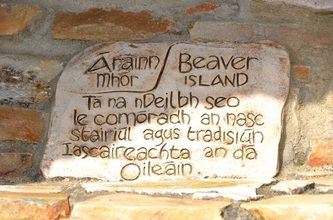

Arranmore Island is twinned with Beaver Island, USA. At Lough Thoir on Arranmore there is a Memorial erected commemorating the connection with Arranmore and Beaver Island (see photograph to the left here).

At the roadside opposite the Memorial there is a beautiful hand made stone Marian Shrine commemorating the Arranmore people who left the island to emigrate. The sign beside the Marian Shrine reads:

"Emigration has been part of life for the people of Arranmore Island for hundreds of years. Many who made the journey across the Atlantic settled on Beaver Island in the Great Lakes of the U.S.A. Of the 881 residents in 1880, there were 141 Gallaghers, 123 Boyles, and 90 O'Donnells recorded in the Census. Strong links are retained today between the people of the two islands.

The memorial at this site commemorates these links"

Nearby is a rather amusing sign which points out to the Atlantic and informs the reader that Beaver Island is 2750.

And the connection with Beaver Island from BeaverBeacon.com

"On the recent visit to Arranmore by 57 Beaver Islanders for the Twinning Ceremony, much of its history was recounted, either by Charlie O'Hara or by those in the party from America such as Paul Cole, who delivered a talk about those sad days on the pier at Burtonport.

Everyone knows that the Famine began with potato blight in 1845, but few realize how close to the edge the people of Arranmore had been living, and how quickly they were overcome. A visitor to the island of 1,300 inhabitants in September of 1845 reported how amazed he was when wretchedly gaunt, half-clothed, and shoeless people rushed up to him with requests for relief.

At that time Arranmore was the property of an absentee landlord, the Marquis Conyngham. He never paid a visit to his holding, instead leaving its administration to Benbow, an English agent who was rarely there either. In the spring of 1846, everyone hoped and prayed that the blight that had devastated the crop the previous year would abate, but it was worse, turning entire fields into a stinking black mass. As hunger increased, Benbow was no help; his only mandate was to meet his quota, an impossible task. To stay alive some normally honest people did whatever they could, driven to hunt for any secret trove of food held by their neighbor. Those caught looting were branded as thieves in any way possible; one woman, a Mary Gallagher, had her ears hacked off as her penalty.

Relief efforts were irregular, and hardly ever reached the distant provinces because of poor roads and poorer methods of distribution. In 1846 a load of Indian meal reached Arranmore, but it was an inedible rancid soggy mess, full of weevils and maggots. That fall a food depot was set up in Burtonport, but there was not nearly enough to go around. The authorities feared that a rebellion would bring them down, and in fact the meager stores were frequently looted before they could be passed out.

Everyone hoped that the worst was over–it had to be. But 1847 brought no relief. The blight continued and, if anything, was worse. Destitute people could be seen combing the fields with rakes, hoping for a single potato to keep the wolf from the door–to no avail. They were dropping everywhere, in the fields, in the streets, or in their homes. Every family had its dead by starvation. The destruction of the potato crop, almost the only source of food, was total. Relief ships, such as the Lame, carrying wheat meal from Belfast, were attacked by starving mobs and stripped of any food in their holds. The police, wanting to make an example, pulled a raid on Arranmore, confiscating everything they found–in their view, it had to have been stolen, and probably was.

To add to their distress, Conyngham judged his island to be unprofitable and petitioned to have it declared a separate Poor-law District. As this was being done, he sold it in 1847. to Charlie Beag, a callous land speculator. Charlie Beag immediately decided to consolidate the farms by greatly reducing the population, which he did by evicting anyone who could not produce a written receipt for their rent. These had never had to be shown before, and when they had been received had not been saved.

To facilitate the eviction, Charlie Beag gave the departing tenants two options. They could go into the poorhouse at Glenties, or they could board a ship for America that he promised would be waiting for them at Donegal Town. Many chose the poorhouse because they were so weak and malnourished that they did not feel they could survive an ocean crossing. But the facility at Glenties was already overcrowded–its death rate was the highest in the country because it had been built in a swamp and flooded much of the year. Even the officials admitted that it reeked of death. Its charges were given clumps of old straw as their bed, with six or seven forced to sleep in a bundle, for warmth, under a single filthy rag. Conditions were so bad that the matron was sacked for dereliction of duty.

The braver ones to be forced off Arranmore went to Donegal Town, marching there on foot from Burtonport to board Charlie Beag's boat–but it was not there! Once again, promises were revealed to be just empty words, issued to get them off his land. There they were, with no money, no clothes, and no food. Hanging around, waiting for a miracle, they began to fall in their tracks. The good people living there did what they could, but there were few options.

Finally a miracle of sorts did take place. The Quakers, one of the few religious organizations to mobilize over the Irish tragedy, sent them a ship–one of the infamous 'coffin ships.' It looked like it would sink, but the hand of God was on them and they made it across the Atlantic in one piece, the ship only sinking on its return trip.

Those who made it to America rejoiced, and sent for their friends. Many settled on Beaver, either directly or after stopping elsewhere first, once the Strangites were dispersed. Seven generations went by, more or less depending on the family, before their heirs sailed back to the island from which they had come, our new Twin. Imagine how their hearts leaped in their chests when they saw, as they approached her shore, hundreds of people waving and playing music and holding up a huge banner simply saying, “Welcome Home!”"

In the little chapel, St. Crone's, the Catholic church on the island, there is a hand carved wooden cross which was given to the islanders by the people of Beaver Island.

Click on any of the photos below to enlarge.

At the roadside opposite the Memorial there is a beautiful hand made stone Marian Shrine commemorating the Arranmore people who left the island to emigrate. The sign beside the Marian Shrine reads:

"Emigration has been part of life for the people of Arranmore Island for hundreds of years. Many who made the journey across the Atlantic settled on Beaver Island in the Great Lakes of the U.S.A. Of the 881 residents in 1880, there were 141 Gallaghers, 123 Boyles, and 90 O'Donnells recorded in the Census. Strong links are retained today between the people of the two islands.

The memorial at this site commemorates these links"

Nearby is a rather amusing sign which points out to the Atlantic and informs the reader that Beaver Island is 2750.

And the connection with Beaver Island from BeaverBeacon.com

"On the recent visit to Arranmore by 57 Beaver Islanders for the Twinning Ceremony, much of its history was recounted, either by Charlie O'Hara or by those in the party from America such as Paul Cole, who delivered a talk about those sad days on the pier at Burtonport.

Everyone knows that the Famine began with potato blight in 1845, but few realize how close to the edge the people of Arranmore had been living, and how quickly they were overcome. A visitor to the island of 1,300 inhabitants in September of 1845 reported how amazed he was when wretchedly gaunt, half-clothed, and shoeless people rushed up to him with requests for relief.

At that time Arranmore was the property of an absentee landlord, the Marquis Conyngham. He never paid a visit to his holding, instead leaving its administration to Benbow, an English agent who was rarely there either. In the spring of 1846, everyone hoped and prayed that the blight that had devastated the crop the previous year would abate, but it was worse, turning entire fields into a stinking black mass. As hunger increased, Benbow was no help; his only mandate was to meet his quota, an impossible task. To stay alive some normally honest people did whatever they could, driven to hunt for any secret trove of food held by their neighbor. Those caught looting were branded as thieves in any way possible; one woman, a Mary Gallagher, had her ears hacked off as her penalty.

Relief efforts were irregular, and hardly ever reached the distant provinces because of poor roads and poorer methods of distribution. In 1846 a load of Indian meal reached Arranmore, but it was an inedible rancid soggy mess, full of weevils and maggots. That fall a food depot was set up in Burtonport, but there was not nearly enough to go around. The authorities feared that a rebellion would bring them down, and in fact the meager stores were frequently looted before they could be passed out.

Everyone hoped that the worst was over–it had to be. But 1847 brought no relief. The blight continued and, if anything, was worse. Destitute people could be seen combing the fields with rakes, hoping for a single potato to keep the wolf from the door–to no avail. They were dropping everywhere, in the fields, in the streets, or in their homes. Every family had its dead by starvation. The destruction of the potato crop, almost the only source of food, was total. Relief ships, such as the Lame, carrying wheat meal from Belfast, were attacked by starving mobs and stripped of any food in their holds. The police, wanting to make an example, pulled a raid on Arranmore, confiscating everything they found–in their view, it had to have been stolen, and probably was.

To add to their distress, Conyngham judged his island to be unprofitable and petitioned to have it declared a separate Poor-law District. As this was being done, he sold it in 1847. to Charlie Beag, a callous land speculator. Charlie Beag immediately decided to consolidate the farms by greatly reducing the population, which he did by evicting anyone who could not produce a written receipt for their rent. These had never had to be shown before, and when they had been received had not been saved.

To facilitate the eviction, Charlie Beag gave the departing tenants two options. They could go into the poorhouse at Glenties, or they could board a ship for America that he promised would be waiting for them at Donegal Town. Many chose the poorhouse because they were so weak and malnourished that they did not feel they could survive an ocean crossing. But the facility at Glenties was already overcrowded–its death rate was the highest in the country because it had been built in a swamp and flooded much of the year. Even the officials admitted that it reeked of death. Its charges were given clumps of old straw as their bed, with six or seven forced to sleep in a bundle, for warmth, under a single filthy rag. Conditions were so bad that the matron was sacked for dereliction of duty.

The braver ones to be forced off Arranmore went to Donegal Town, marching there on foot from Burtonport to board Charlie Beag's boat–but it was not there! Once again, promises were revealed to be just empty words, issued to get them off his land. There they were, with no money, no clothes, and no food. Hanging around, waiting for a miracle, they began to fall in their tracks. The good people living there did what they could, but there were few options.

Finally a miracle of sorts did take place. The Quakers, one of the few religious organizations to mobilize over the Irish tragedy, sent them a ship–one of the infamous 'coffin ships.' It looked like it would sink, but the hand of God was on them and they made it across the Atlantic in one piece, the ship only sinking on its return trip.

Those who made it to America rejoiced, and sent for their friends. Many settled on Beaver, either directly or after stopping elsewhere first, once the Strangites were dispersed. Seven generations went by, more or less depending on the family, before their heirs sailed back to the island from which they had come, our new Twin. Imagine how their hearts leaped in their chests when they saw, as they approached her shore, hundreds of people waving and playing music and holding up a huge banner simply saying, “Welcome Home!”"

In the little chapel, St. Crone's, the Catholic church on the island, there is a hand carved wooden cross which was given to the islanders by the people of Beaver Island.

Click on any of the photos below to enlarge.

Later, in the mid 19th century, the island was bought by a man from county Antrim by the name of John Stoupe Charley who in 1855 built "Glen House" which is now the Glen Hotel. In 1893 following the collapse of landlordism the island was returned to the state and transferred to the Irish Land Commission.

GOD'S TEAR

God's Tear

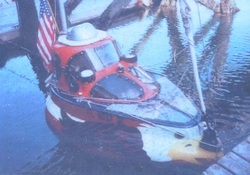

In 1982 a small craft landed on the rocky shoreline at the cliffs of Arranmore after being caught in a storm at sea. The craft, God's Tear, and skipper Wayne Dickinson entered the records as being the smallest ever craft to have crossed the Atlantic and although this record has since been broken, it remains the first to make the perilous journey in such a tiny boat. The photo to the left is of Gods Tear and taken from the information sign at the cliffs.

From the sign at the cliffs:

"On the 31 October 1982 Wayne Dickinson left Boston, USA, to cross the Atlantic in his tiny 8' 9"" craft Gods Tear. After 142 days at sea he was caught in a force 10 storm and was smashed onto the rocks of Arranmore Island not far from where you are standing. Wayne then walked to the Lighthouse where he was found later that day by a local man, Charlie Boyle.

At that time, Gods Tear was the smallest croft ever to have crossed the Atlantic but this record has since been broken."

Click on any of the photographs below to enlarge.

From the sign at the cliffs:

"On the 31 October 1982 Wayne Dickinson left Boston, USA, to cross the Atlantic in his tiny 8' 9"" craft Gods Tear. After 142 days at sea he was caught in a force 10 storm and was smashed onto the rocks of Arranmore Island not far from where you are standing. Wayne then walked to the Lighthouse where he was found later that day by a local man, Charlie Boyle.

At that time, Gods Tear was the smallest croft ever to have crossed the Atlantic but this record has since been broken."

Click on any of the photographs below to enlarge.